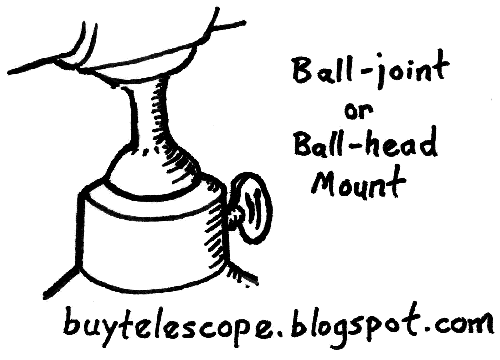

The Ball Joint, or Ball-Head Mount

These do a poor job of holding the scope, and even if they have a locking screw, it's not possible to point the telescope accurately or to move it to compensate for the motion of the Earth. In some cases a ball joint may be usable for a camera piggybacked on a telescope (on a good equatorial mount) but it's not adequate for any sort of telescope used for astronomy, even small ones. Personally, I would avoid even low-power spotting scopes that come with this type of mount.

Camera-Style Tripod Mount

Again, these aren't adequate for an astronomical telescope. Pointing them at what you want to see is way too difficult. Trying to compensate for the Earth's motion is nothing but frustration. These mounts are OK for cameras, binoculars, and small spotting scopes that give about 20-25 powers of magnification used for terrestrial purposes. They're not well designed for viewing at high angles, so they're not all that useful for astronomy with any instrument. With binoculars they're tough to use because you have to lean forward over the tripod to get your eyes up to the eyepieces. It's not a comfortable way to look through binoculars, and if you can't relax and enjoy the view you're not going to enjoy astronomy.

Cheesy Fork Mount

There are good fork mounts. They are solid, provide smooth motion, and hold the telescope on what it is pointed at. The fork mounts used on most Schmidt-Cassegrain and Maksutov telescopes are quite good.

And there there are monstrosities like the one pictured above. These are still common on many small inexpensive telescopes. They don't move smoothly, they have slack areas where the scope flies through and tight areas where the scope only moves with dificulty, they don't hold the scope in place even if they have impressive-looking slow motion or other support bars. They're junk. If you've already got a scope on one of these, look at retro-fitting it with a nice homebuilt Dobsonian-style mount or some other good mount suited for the telescope.

Mind Killers

If you want to kill a kid's interest in astronomy and science, buy them a telescope on one of these mounts. If you want to convince them (or yourself) that you're incompetant, and that astronomy is difficult, march right into your local camera shop or "Mart" store and pick up a telescope mounted on one of these.

Some newer mounts have lots of fancy molded plastic around them to hide the fact that they are still one of these cruddy mounts underneath. Lots of little refractor telescopes come on a mount that has a bulgy plastic clamp that goes around the telescope and big plastic handles on the motion controls. It's still just a camera mount.

Don't be fooled into buying one of these. No telescope at any price is a bargain when it's sold on one of these. It's not worth buying and thinking that maybe you'll get some light use out if it and upgrade later "when you get serious." You'll never get started with one of these.

Remember, the mount is more important than the optics of the telescope itself. So-so optics on a solid mount will give you far more use and enjoyment than excellent optics on a lousy mount. When you go shopping, don't ask about magnification, don't ask about aperture or light-gathering power, don't worry about accessories. There are three things you want to know about: The Mount, The Mount, The Mount. If you've got room for 4, I'd recommend staying away from telescopes that use .965 size eyepieces. It's often a sign of a cheap, useless scope. Go for something that takes a 1-1/4" eyepiece. After you find one on a good mount.